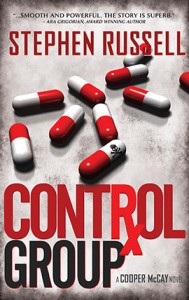

Explore the Power of Pharmaceutical Companies in this Frightening Medical Thriller

Mackie’s past and future collide

In the spring of 1993, young Dr. Cooper “Mackie” McKay stands on the cusp of a bright surgical career. He has the power of digital data and the potential for revolutionary cures at his fingertips until a paralyzing family tragedy shatters his dreams. The only way to restart his promising career—and revive his marriage — is to step away. A temporary position at BioloGen Pharmaceutical offers refuge. His charge is to convince other doctors that the billion dollar blockbuster drug Anginex, in the final stages of testing, is both safe and effective. He quickly learns otherwise.

He is soon forced to choose between the drug company with a promising cancer cure and an FBI informant with his own versions of the truth. Now Mackie must do whatever it takes to get out of harm’s way before the story breaks — billion-dollar drugs don’t go down without a fight.

Order at:

Read an excerpt

Chapter 1

Spring 1993

O n a sunny Saturday afternoon in Maryland, Dolores Gonzales didn’t expect to go to the National Institutes of Health to die, and Dr. Scott Hoffman didn’t know that he would kill her. He waited in his office, tapping his foot to the island music in his head while scanning her chart. His mind wandered from the drug study to thoughts of retirement. One last clinical trial.

One final weekend of work.

Hoffman picked up his dictaphone to complete the final entry for her chart. “This next dictation is for study subject number one-three-six-two. Name is Dolores Gonzales. She is a forty-two-year old, Hispanic female here for the final safety evaluation. Ms. Gonzales began the trial nine months ago, and presently she is…”

A loud metallic crash interrupted Hoffman, followed by the thud of footsteps racing down the hall. He straightened. His of ce door slammed open against the wall. Framed diplomas rattled.

“Jesus, Jason! What the hell’s going on out there?”

The tall research assistant stumbled in, shirt untucked, dark-rimmed glasses askew. Jason gripped the doorframe for balance. “Dr. Hoffman, I need you. Ms. Gonzales can’t breathe.”

Hoffman grabbed his lab coat from the back of his chair. “She was ne last week.”

He stepped into the hallway and froze.

Dolores Gonzales leaned against the wall, gasping for breath. This could not be the same woman he had seen only one week ago. Sweat glistened on her bloated face. Hoffman heard her drowning in her own phlegm. When she looked at him, he saw terror in her eyes. She crumpled to the oor.

Hoffman kneeled beside her to find her pulse. “Hold still, Ms. Gonzales. We’ll take care of you.” He glanced up at Jason. “Grab the crash cart. Now!”

In the brief time it took for the research assistant to return with the resuscitation equipment, Dolores Gonzales’ heart slowed. The frantic pounding of her carotid pulse eased to an irregular tap against Hoffman’s ngers. He attempted chest compressions, but his hands slipped on her sweaty body, causing him to put pressure on her stomach. Frothy sputum splattered his cheeks.

“Call a code!” Hoffman yelled.

He grabbed a central line kit from the crash cart. Swiping an alcohol pad over her chest, he plunged a needle in. Purple blood dribbled onto the oor, a visible reminder that her heart possessed neither the oxygen nor the intensity to keep her alive. Hoffman threaded the guide-wire through the needle and slipped the long IV cannula over it. He pushed a syringe full of epinephrine into the IV and then resumed chest compressions.

What would happen if the FDA found out she died while taking the study drug?

As Hoffman worked, the code team, an army of blue scrubs and stethoscopes, raced toward him. He pumped harder on her chest. Red secretions gurgled up from her lungs, indelibly staining his white coat.

Oh, my God, he thought. What have I done?

Six hours later, with unprecedented cooperation from the coroner, Hoffman stood over his dead patient. The scent of death and formaldehyde permeated the room. He usually let others oversee autopsies. Tonight, he forced himself to get involved. Too much was at stake.

He locked his knees and concentrated on the open abdomen that glistened before him. Anything to avoid the face of the deceased woman. Sweat soaked his scrubs. His face mask pressed against his goatee. The spotlight above the metal table warmed his shaved scalp as it illuminated the body in front of him. Hoffman placed a gloved hand on the table but avoided touching the corpse.

“Would you look at that?” The pathologist looked up from across the table. Chest hair sprouted over the top of his scrubs like grass around a sidewalk and spread up his neck. The surgical mask muf ed his voice when he spoke. “Something destroyed her liver. Check out all these divots and pits.” He pointed to a purple mass of esh that looked more like a sea sponge than a smooth organ.

Hoffman nodded. “What do you think that’s from?” “Any number of things. You say she’s a diabetic?”

“For years.”

“We don’t see this kind of destruction from diabetes. Look at her, though.” He slapped the side of the body, shaking the corpse. “A woman this fat is going to have fat in her liver, too, but this looks drug-induced. Remind me what meds she was taking?”

Hoffman carefully chose his words. “She was on insulin for a long time…”

“That wouldn’t do it.”

“And on some oral meds recently for diabetes.” He became dizzy, and gripped the table for support.

“Careful. I don’t want you puking all over my morgue. If you want to sit down or pull up a chair, that’s okay with me.”

“I’m ne.”

“Suit yourself.” The pathologist pointed to another area on the mangled liver. “It’s supposed to be smooth and shiny, but all this blood indicates ongoing hemorrhage. There’s blood pooled in the abdominal cavity, too. That’s unexpected.”

Hoffman nodded. To get the results he wanted, he needed to stay engaged. And focused.

“Which group was she in?”

“Excuse me?”

“Was she in your study-drug group or the control group?” “Control group,” Hoffman lied. “I checked before I came down here.”

The pathologist shook his head. “You don’t see this from a sugar pill, I can tell you that.”

Hoffman straightened, emboldened by his lie. “Her chart said she’d been taking other prescription meds outside of the study protocol.”

“Like what?”

“Pain meds. Aspirin. Surely that contributes to what we’re seeing.”

The pathologist nodded. “Could be, but it’ll be weeks before the toxicology report comes back.” He removed additional slices of the liver and placed them in a specimen tray. “I’m just about done down here. You want to stay while I examine her brain?”

Hoffman felt his insides lurch. “No, thanks. I’ve seen all I need in order to nish my report. I’m heading back to the of ce to update her family.”

When he reached his of office, Hoffman saw a janitor cleaning the hallway. The crash cart rested against the wall and the oor sparkled under the mop. As far as he could tell, no evidence remained of the afternoon’s grisly events.

He walked into his of office and closed the door. The stench of the morgue lingered on his hands. Hoffman glanced at the rows of charts lining the door and at the small stack of manila folders on his desk. We should have finished by Monday, he thought. Hundreds of patients had sailed through the trial without any problems. Now this. There was still a chance that her death had come from something else. As long as the pathologist believed her to be a member of the control group, the autopsy report shouldn’t implicate the study drug.

Hoffman sat down at his desk in front of the open chart of Dolores Gonzales. Calling her family would have to wait. First, he would complete her chart. He pressed the rewind button on the dictaphone. “This next dictation is for study subject number one-three-six-two. Name is Dolores Gonzales. She is a forty-two year old female enrolled in the phase three study…”

He stopped the tape. Hoffman massaged his temples.

This was the right thing to do, he told himself. The medicine had potential. Thousands of patients would bene t from the drug. He enjoyed an impeccable record as an NIH researcher, which was why the company had hired him to steer this drug through its clinical trials. He tried not to think about his six- gure payoff once the drug received FDA approval.

He pressed record. “The patient missed her last appointment, and she has been lost to follow-up.”